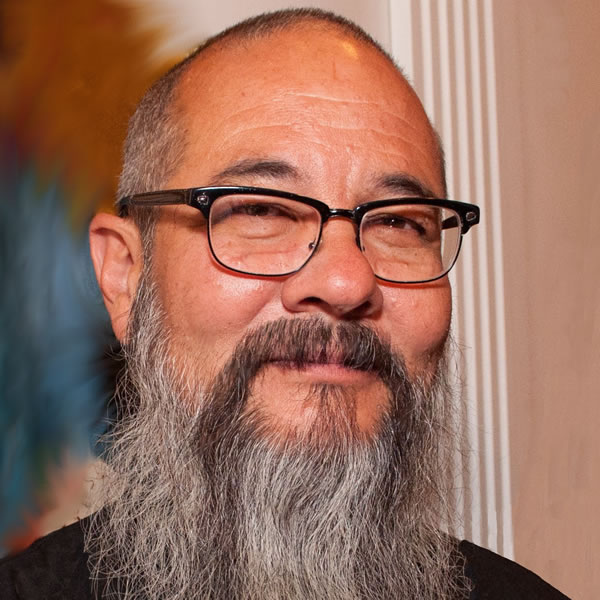

Steve the Builder

Fr. Meletios Webber on Priesthood and Spiritual Fathers, Part One

Steve interviews Fr. Meletios Webber, the Abbot of St. John's Monastery, on what the "grace of the priesthood" bestows on a man and what the priest's authority and role is in the life of the parish and in his relationship with his parishoners as his spiritual children.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Listen now DownloadSupport podcasts like this and more!

Donate NowTranscript

Sept. 28, 2010, 5:46 p.m.

Steve: Welcome to this edition of Steve the Builder. We have kind of a special treat for you for the, probably the next three podcasts, because I had the opportunity to spend about an hour and a half with Fr. Meletios Webber the abbot of St. John’s Monastery in northern California where I did a series of podcasts while I was sheet—rocking and dry—walling and painting the new church building up there last year. And as long as he was here I thought he’d be the perfect person to talk to about an issue that puzzles a lot of us converts and has in fact puzzled me for about the last twelve years, and that is, what exactly does the grace of ordination give to a man when he becomes a priest and what, exactly, is the role of the parish priest in the life of the believer in terms of spiritual fatherhood, spiritual direction, confession, and all those kinds of things.

So Fr. Meletios has a unique background that I think he could bring to this. He’s been Orthodox for I think some forty—odd years. He’s a convert from Methodism, went to Oxford, he’s a spiritual son of Kallistos Ware, his pedigree runs around Elder Sophrony and Anthony Bloom. He spent some time in a Greek monastery on Patmos, he’s been a parish priest in America, he went to Bozeman, Montana where he got a doctorate in psychology while he was the parish priest of a Greek parish there, then he spent a few years as the chancellor of the Western Diocese of the Greek Church under Metropolitan Anthony of blessed memory, then he was the pastor of a Russian Church in Holland where he was planning on spending out the rest of his days, when he got a call from the now Metropolitan Jonah to come and take a look at becoming the abbot of St. John’s Monastery to replace him when he was called to be a bishop.

So Fr. Meletios brings a lot of experience, a lot of maturity, and a lot of background to this question. He’s not merely an academic, his formation has been broad and has been :wide and it hasn’t just been from reading books, and it’s multi—national. So with all that pedigree on the table, I’m just going to launch you listeners right into the interview. So here’s the first installment of the interview with Fr. Meletios Webber:

(Interview begins)

Steve: Well good afternoon and welcome to this edition of Steve the Builder /Our Life in Christ. I’m being schizophrenic today because I don’t know exactly which place this is going to go on the Ancient Faith Radio podcast but I’m sitting in my best friend of years and years and years Allen Boyd’s dining room with Fr. Meletios Webber from St. John of San Francisco’s Monastery in northern California. He’s down here for the weekend and just gave a spiritual retreat at one of our local parishes which we did record and will be available on their bookstore web site in probably about three weeks. I highly recommend it and we may post some excerpts from it on the podcast on a later day so you can kind of get a flavor for some of the presentations.

So, Fr. Meletios, I know we got you up from your nap this afternoon—well, now we just did. Welcome to the program and it’s a joy to be able to speak with you.

Fr. Meletios: Thank you.

Steve Let me kind of frame the discussion here for the listeners. We just did a little bit of talking off the microphone before we turned on the computer. One of the things that, over the years—and I’ve been Orthodox for twelve, thirteen years now—and one of the things I’ve encountered over the years and I think makes up a good deal of the email I get from podcasts and ministries I’m involved in, regards two things and one of them is what to do about a spouse who doesn’t want to convert to Orthodoxy and that’s an entirely other program, but the other one that I really wanted to talk to you about because of your background is what exactly is the role and the place of the spiritual father in the life of the Orthodox Christian. This, over the years, has taken on an almost mythical character, I think, among converts. We read a lot of books, we read about the Optina Elders, we read St. Ignatius Brianchaninov- is that close enough? And The Way of the Pilgrim, we read the Athonite Elders, and we’re all of the sudden on the quest for a clairvoyant elder. And it seems like we need this person who can see into our souls, who can read our thoughts, and who can dissect the nuances of our spiritual illnesses and give us precise spiritual advice, maybe some precision in penance, the exact number of prostrations that we need to be doing, or something like that in order to overcome our spiritual illnesses.

The bigger picture is, what is the role of the parish priest in all of this, because, of course, all of the bishops I have ever been under and I’ve been under three different ones have said your parish priest is, by default, your spiritual elder, or your spiritual father, and that is the person that you should, barring any strange circumstances or something unique to your situation is the person you should be confessing with. I know locally, because we have St. Anthony’s Monastery so close by and now we have St. Paisius close by, there are not a few people that go out to the monastery to receive their spiritual direction. So, this creates some tension. People come back from the monastery and tell all the other people in the parish “You really should be going out to the monastery because I’m getting this kind of advice from the elder there and you would be so much further along like I am, of course, if you went there.”

So, with that kind of a framework, let’s begin with, I guess, the fundamentals of spiritual fatherhood. One of the statements that I just recently saw on an internet discussion is when a man is ordained a priest the Holy Spirit makes up that which is lacking in him, period. Can you address exactly what that means, when a man is ordained receives the gift of the Holy Spirit in terms of ordination? What exactly is made up or what exactly is lacking that is added by the Holy Spirit? Because that’s a very broad, wide—open statement.

Fr. Meletios: Right. And I think to answer it with any clarity we need to look at the big picture first and then come to the specifics of that question and to see the life of the Church as something which is ever-evolving. The relationship, a tightness, the closeness of the Christian community has been different at different times over the ages. In the very beginning of the Church, joining the Church was tantamount to putting your life on the line. There was a large danger that you would be executed for belonging to the Christian Church and this gave the early Christians a very strong sense of identity and a bond with each other which is difficult to imagine under other circumstances although we do see cases of it, very similar cases, in, for example, the Communist regimes of last century. After the Church became the preferred religion of the Roman Empire under Constantine, that tightness gave away to something completely different. The Church almost became an arm of the state and far from being a danger to anyone to join the Church, it became almost socially acceptable, socially preferable, even.

Steve: Even advantageous.

Fr. Meletios: Yes. So people’s motivations and the level of commitment obviously changed. And in the history that has passed between then and now this has gone through many modifications, one way or another, during periods where, for example, there was a domination by a non—Orthodox religious political force, then the Church tended to be close-knit and very inward—looking, out of necessity. In other periods where the Church has been pretty much hand— in—hand with the government as it was, for example, at the time of the Byzantine Empire, things were much looser and there was much less demand on the individual to live strictly according to certain precepts. This is neither good or bad, this is just how it was. I don’t think we need to worry about whether it’s right or not.

So the relationship between a particular person and his parish priest has undergone many variations over the centuries. And what we are seeing today is not necessarily new but it tends to be something which is unique to the situation of today. So the question you asked, “How does a man change when he becomes a priest?” has to been seen in some sort of context. What does the parish community expect of this man, what does the bishop expect of this man and so on and what does outside society in general expect of this man?

The words used, do in fact, suggest what you said as a way of understanding what’s going on. The Holy Spirit makes up what is lacking in the candidate for whatever office it is he is being ordained to. But I think we have to be quite clear that Orthodoxy is very straightforward in its expectations of ordination. In some other Christian traditions, notably the Roman Catholic Church, there is the notion that at ordination some power is given to the candidate, some power that he didn’t have before. While this isn’t entirely ignored in Orthodoxy, it is not the main picture of what’s going on . The main event at an ordination is that a man is being set aside for a specific task. I think this is most clearly seen in the village situation in any medieval country where a priest worked his entire life. Monday through Friday he would go out to the fields with his neighbors and look after his flocks or his land and but on Sunday his neighbors would put on their best suits and he would go to church and put on his vestments and would serve the Liturgy for the community as best he could, sometimes with little or no education, sometimes simply using whatever knowledge he had to his best advantage in allowing the community to take part in the Divine Liturgy, for which a priest is necessary, obviously.

When that man dies, the community gets together and has a little think about who will be the next priest and it’s usually another member of the community and it may, in fact, be the son of the priest who has just died. That’s not at all uncommon, and at that point the man is sent to the bishop and the bishop examines the person to find out if there are no canonical reasons why he cannot be ordained—that list is quite long and complicated. And there’s something else there that happens there that I want to come back to in a minute. And then, all being well, the man is ordained. Perhaps he stays around the bishop for a while in order to learn the services and in order to be taught what exactly he needs to learn. Then he goes back to the village and takes on the role of the priest.

So the priesthood for us is a man who is specifically set apart in order to perform a particular service, diakonia, ministry to the community.

What I want to come back to is quite an interesting sort of thing because it shows that there’s a two—dimensional or two ways of looking at this process. One is the relationship between this man, the candidate, and the bishop, and the other is between this man and the spiritual father. And this is the one place in the life of the Church where a spiritual father has a sort of an official role. Usually the notion of spiritual fatherhood is sort of charismatic and sort of ad lib. Someone may or may not have a spiritual father at any given period of time and that’s just how it is. But in order to be ordained, the man has to go to a spiritual father, someone that he knows, and the process is usually, although not always, to give a life confession. Part of that process is to allow the man to turn over a new leaf, to start a new life, which is the pastoral thrust of what’s going on there. And part of it is to see whether in fact there are in fact canonical impediments to his ordination.

So the process of towards ordination is on two paths. One, the official path, which is hierarchical and is of the power of the bishop, and the other, which is charismatic in nature because the man can choose his own spiritual father and depends on the relationship between himself and that spiritual father. To this degree the bishop is not the spiritual father. It’s usually a priest, someone else. That balance is something that which needs to be seen in the life of the Church, I think, in general. That there is a hierarchical structure in the Church which shows how things happen safely. The bishop is the archpastor of the diocese, the parish priests are his representatives in the parishes and so on, and the life of the Kingdom is then transmitted, as it were, from the diocesan middle, the bishop through his priest, to his people.

The priest never, incidentally, stands at the altar by right. The most an Orthodox priest ever does is to represent the bishop. And the presence of the antimension on the alter is an indication of that fact.

But there is also, as the practice suggests, the second notion that there is another sort of structure going on, the spiritual structure where a person is free to choose his own spiritual advisor, to discuss problems with him, to get support from him, if need be to get some direction from him and under extreme circumstances, I would say, to receive some sort of remedial advice from him in the form of- penance is not the right word because that doesn’t belong to our system at all. The word is epitimia and it suggests something like a directive, but I would have to say that these epitimias, these penances, if we to use that word, have to be used with extreme caution. But let’s talk about that…

Steve: Yes, that’s something I want to address at a later time.

Fr. Meletios: So what does the man get when he is kneeling there on one knee if he is being ordained deacon or on two knees if he is being ordained priest or on both knees plus the Gospel on his head if he’s being ordained a bishop. Well obviously, his personality is not affected by ordination. That is not in the way of God’s working. Specifically what the man receives through the grace of the Holy Spirit is the ability to do what the Church needs him to do in his new service, in his new diakonia. So from that point on, a deacon has everything within himself that he needs in order to be a deacon. The priest, the same for what he needs to be a priest, and so on.

Steve: Okay now, can I ask you a question here. I was tonsured a subdeacon a couple of years ago and one of the requirements for that was to be able to intone the Epistle and to read well.

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: I can guarantee you that after my tonsure I didn’t read any better or…

Fr. Meletios: No

Steve:… was not able to sing any better than I was beforehand. So when you say that a person is equipped to do the ministry that he’s been ordained to, what specifically are you talking about there?

Fr. Meletios: He has the authority to do what the Church requires of him in his new situation. So the priest has the ability to lead the congregation for the Divine Liturgy as long as he has the blessing of the bishop to do so, he has the ability to bless the congregation, he has the ability to teach the congregation, to a limited extent. But his personal character, his personal life- these things need not be touched at all, in any automatic sense. One would hope that the Holy Spirit is able to work miracles even with what … the peoples he’s working with, but that’s not the issue here. There’s no automatic guarantee that the person’s character will change and there’s certainly, certainly no indication that he will suddenly be right about everything. That isn’t given to anybody in the Orthodox Church, even the Patriarch is allowed to be wrong about things.

Steve: So when I heard a parish priest say that when he is vested that every word that proceeds from his mouth is from the Holy Spirit and that what he says in his homily is as important as the Gospel itself, is that what the Holy Spirit does with somebody? When I heard that then I thought, well, what then about all the heretics who were vested and teaching in their parishes? Does the Holy Spirit guarantee that the man becomes an infallibly representative of Orthodoxy by virtue of ordination?

Fr. Meletios: Absolutely not and you don’t really need to use much imagination to see why. I would say that he may have a point in that he should be aware that when he is wearing the vestments he is representing the Orthodox Church to whomever is there and that he has to be extremely careful to show the life of the Gospel, the life of the Kingdom to his people during those times that he is functioning, in that very full sense, as a priest. An enormous responsibility is placed on his shoulders together with the vestments. But as to giving him any personal infallibility, that’s, that’s not true at any level for anyone, that’s not to the experience of the Orthodox Church, at all, none.

That doesn’t mean that a person in a position of authority—a priest, a parish priest, a bishop—doesn’t have to give directives sometimes to his people. Otherwise, why would he have to be there?

Steve: What would be the point, yes.

Fr. Meletios: And sometimes he’s going to do that with some force, just as the father of a family, perhaps, at times needs to discipline his children. That doesn’t necessarily mean, thought, that the man is right. It does suggest that he sort of has the right to do his best but he may not be right at all, he may be entirely wrong on any given theme. So when a priest sometimes has to give, say, directions to a parish council that seems to be completely out of control, then the Church would say, “Well, he has the right to do his best to explain what the Orthodox Church does in a situation like this” because very often people don’t really know. But as for any personal infallibility then the answer would have to be absolutely not.

Steve: And I think that kind of touches on some kinds of things that are spider—webbing out from the core issue. I’ve been in enough different parishes and on parish council for the entire time I’ve been Orthodox and a number of the issues that have come up with priests have been exactly in, you know, those kinds of situations where the priest’s experience of Orthodoxy was perhaps from his personal background, from his experience in, perhaps, being raised Orthodox in a specific culture and trying to bring a large group of converts into his experience of the Church when we’ve come from Episcopalian backgrounds, or Congregational backgrounds where the priest didn’t have that kind of authority. I felt like we were having more of a cultural clash than we were a clash of necessarily authority.

Fr. Meletios: And I thing it’s actually worse than that because the Orthodox Church, with some exceptions in certain periods of Russian history until the last century or so, had no idea what a parish council was. It’s not part and parcel of Orthodox life throughout the centuries. Various levels of participation by the laity in the running of the Church have been seen in the history of the Orthodox Church but during many long periods no such thing has existed at all. And the introduction of parish councils actually adds a problem to, you know, the question of what is the Church actually like? I’ve experienced this, for example, in western Europe where I was in a parish for a while where the priest was trying hard to get the notion of parish council accepted by the people and then used in a way that was acceptable to the Church, because both things have to happen. What you tend to get, first of all, is when the people realize they can have some influence and authority which they never actually experienced before, then they go overboard and think well, we’re running the Church and we can hire and fire the priest, which, of course, is simply not true. A priest is placed or removed only by the bishop. That’s the practice of the Church. There have been elements of congregationalism that have crept in. I’ve seen parishes in this country that treat a priest like, pretty much as, you know, as…

Steve: A hired hand

Fr. Meletios:… the hired hand to the parish council. And that is not the Orthodox practice. But these people don’t know that unless they’re told. Very often they don’t want to hear. By this point there’s a lot of ego involved and usually no one is listening and everyone’s talking. So there are problems there, too.

Steve: So when we have a situation where we have a conflict between at times, the collective wisdom—or the collective egos—of the parish council are in conflict with the discernment or the sensibility of the priest who the direction the parish has to go … how can that work?

Fr. Meletios: The structure across the different jurisdictions is pretty much the same. Parishes are grouped into deaneries, deaneries become part of a diocese, and the diocese is part of the national Church. So, the way to deal with any conflict is first of all to use that structure. If there is a struggle between a parish council and a priest over something trivial or something terribly important, then the first person to be consulted would be the dean of the deanery. If he can’t solve it, then the bishop may or may not get involved or the bishop may appoint somebody to mediate. But there is always a structure in place for this to happen. Once you’ve got parish councils and things like that then you need a structure all the way up. And that’s what the Church in America has done. And this isn’t a bad thing. I think the spirit of America has something vitally important to add to the experience of the Orthodox Church, at least in America. And this notion of sharing of power, checks and balances, is something which I think gradually will become an integral part of our Orthodox life. But in getting there, there are many bumps and grazes and a lot of people are going to be saying a lot of bad things. That’s how we do things. Of course, if the ego were not involved, if we could do this all a spiritual way, it’d be a lot smoother but I haven’t noticed this happen too often at a parish council.

Steve: It doesn’t happen much on any human level.

Fr. Meletios: No.

It is true that across the board you can see at times that the tension is there, that is there, actually works to the advantage of the whole.

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: There’s a necessary tension. Alternative viewpoints are able to be expressed…

Fr. Meletios: Yes

Steve:… and communicated throughout the parish because of that tension at times and if the people involved are grownups about it, it can work to the advantage of all.

Fr. Meletios: The trouble is when people get into conflict they stop being grown up…

Steve: Exactly.

Fr. Meletios: … and very quickly become like children and not very nice children, either. Our Church is hierarchical, that is not going to change, but how we understand the role of the hierarch in feeding his flock, that may well be given a new coat of paint as the Church becomes more American.

Steve: You see the direction of the American Church becoming more accountable. I take it “accountability” seems to be kind of the watchword among the archdiocese now. You know, the recent scandals with…

Fr. Meletios: There’s been scandals?

Steve: Oh, that’s right, you’re in a monastery, you’re unaware of those things (laughter).

But anytime you introduce accountability into a system that’s been in place for centuries…

Fr. Meletios: It’s a rough ride.

Steve …it’s a rough ride. And the nuances of how to work that out. Of course as you say, the egos of those who are now held accountable and those holding account, there’s a great opportunity for ego display on both sides of that equation.

Fr. Meletios: Absolutely. And we see it, unfortunately.

Steve: Yes.

Fr. Meletios: Quite often. Not when the Church is being the Church but when the Church is misbehaving. When the Church misbehaves it’s neither better or nor worse than any other institution that’s misbehaving. And we have to face that reality, but it is never the whole picture of the Church.

Steve: Yes.

Well, that’s all we have time for today. I have another hour’s worth of material. This week we talked more in terms of the priest and his relationship to the congregation and the parish. Next week we’ll begin the discussion of the priest with the individual parishioner and his spiritual children. So thank you for listening this week. We’ll see you next week on Steve the Builder.

About

Steve Robinson is heard regularly on Our Life in Christ with his co-host Bill Gould. But in this shorter podcast, Steve reflects on the practical side of being an Orthodox Christian working in a secular environment.

Contributors

Steve Robinson

Steve Robinson