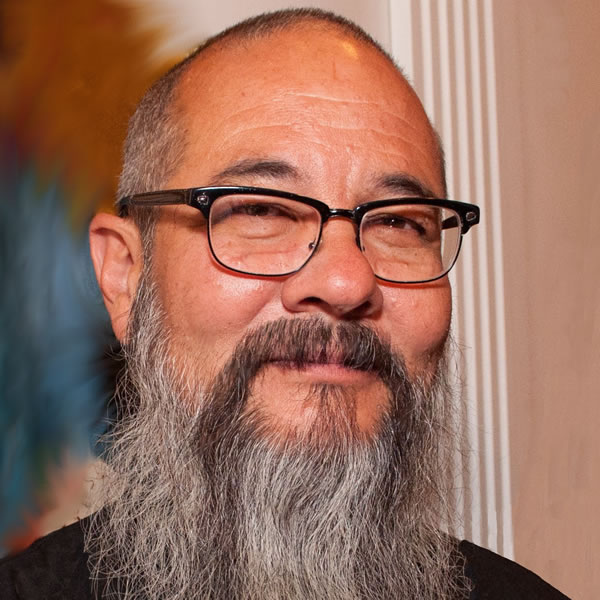

Steve the Builder

Fr. Meletios Webber on Priesthood and Spiritual Fathers, Part Two

Steve continues his interview with Fr. Meletios Webber and they discuss the role of the parish priest as a Father/confessor, confession and counseling, penances, clairvoyance and much more.

Monday, February 7, 2011

Listen now DownloadSupport podcasts like this and more!

Donate NowTranscript

Nov. 4, 2010, 12:57 a.m.

Steve: Welcome to this edition of Steve the Builder. Last week I posted the first part of the interview with Fr. Meletios Webber on “Everything You Wanted to Know about the Priesthood and Spiritual Fathers but were Afraid to Ask, or Possibly Didn’t Know to Ask.” So without any further ado we’ll jump right back into the interview. So here’s Fr. Meletios.

Steve: We’ve been kind of talking on an institutional level here a little bit but on a more personal level, the role of the parish priest in the life of the parishioner, or the life of the individual. The default direction of the bishops to all of us in every parish I’ve ever been has been that your parish priest is your default spiritual father unless there is something unique or special about you in some way, that should be the man that you go to for confession, for spiritual direction, and spiritual advice.

Fr. Meletios: Yes, although it depends on the circumstances a great deal. I think if you are in a city, such as here in Arizona, for example, people are quite capable of going to another church for confession, for example. And I don’t see anything wrong with that at all. In most Orthodox countries you wake up in the morning and you hear bells from what, six different churches and then there are five monasteries within twenty miles and you may go to this monastery for Liturgy and to that monastery for confession and that parish for the sermons and such a thing.

One of the things that the American Church has to get used to is that the parish unit has no real Orthodox roots. The unit is the diocese in Orthodoxy. And within the diocese you are free to choose, like at a buffet, where you go and how you portion your spiritual effort. In Greece there is almost no notion of belonging to a particular parish.

Steve: Really?

Fr. Meletios: It just doesn’t exist. People may go to the same church all of the time but what’s to belong? I mean, where you light your candles, does that make you the belonging? It’s because we here have the system where we need to pay money into a fund in order to pay a priest, that lends itself to what we’ve used to in America, which is the individual congregation doing its thing and running its own affairs. That is not Orthodox. Also the notion that you belong to one parish and not another is not Orthodox.

Steve: So you belong to a diocese…

Fr. Meletios: You belong to a diocese. And I would say that here in the United States you are also free to go across jurisdiction. There’s nothing in the beliefs of the Orthodox Church, per se, which stops a Greek Orthodox from going to an Antiochian parish for confession, for example. Now it may be that the parish priest would like to know that you have gone to confession to somewhere else. That’s possible.

Steve: And that’s what I’ve heard, is that the role of your parish priest is to oversee your spiritual life and therefore…

Fr. Meletios: Right…

Steve: …he would need to know if you’re, say, being a serial adulterer, so he would know whether or not to commune you. And so if you were taking communion in one parish and confessing these heinous sins to another priest then he would not have that knowledge.

Fr. Meletios: Yes, that’s a rather gray area because the confessor priest in that case is not free then to communicate what he has learned to the parish priest necessarily. But that’s a problem the Church has always lived with. That fact that things have to be kept confidential is more important than the fact that people have to be kept in line. So sharing confessional secrets, for example, is simply not allowed under any circumstances. That’s simply not what we do. Someone going to confession needs to know that they are safe in order to confess what they’re going to confess. There may be canonical repercussions to something he says in confession and then the priest has to ask the person concerned if he wants to talk to another priest or if he wants to talk to the bishop and that sort of thing. Quite how you go about this if the person says “No” I’m not sure, but think about it: is such a person likely to exist? Coming to confession in the first place would presuppose that the person has a notion of the life of the Church and wants to live within the grace of the Holy Spirit, so to thwart the process by refusing the priest to do something which looks pastorly positive doesn’t really make sense. This is a hypothetical ….

Steve: Right, right. My notion has always been that if I didn’t want penance then I just wouldn’t go to confession.

Fr. Meletios: Right

Steve: If I had to risk getting one that I wasn’t…

Fr. Meletios: Right

Steve: … willing to fulfil.

Fr. Meletios: And we need to, I need to say again that the giving of an epitimia is not an essential part of confession, never has been, and needs to be looked at with very great care. I talk about this with many people including many bishops.

Steve: Well as long as we are on that path right now…

Fr. Meletios: Okay

Steve: …can we talk a little bit about that?

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: This is one of the issues that I’ve gotten email about from people and it is the fodder for the questioning of the validity or the wisdom of having their particular priest as their father confessor is they have gotten what they believe is some strange or questionable or offensive or just mysterious, to them, spiritual direction or ….

Fr. Meletios:Yes.

Steve: …or penance of some kind. An extreme example, you know, a young man who gets a three-month excommunication for masturbating and then goes to another parish priest who says “What?!” …

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: …and of course the one priest who gives the penance understands that to be the tradition of the Church…

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: … and the priest who says “What?!”

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: … understands that not to be the tradition of the Church and so now the new convert is in the position of saying “One of these priests is goofy.”

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: … and how do I discern? Is it my spiritual short-coming that I’m not able to fulfil this penance and I am never going to be able to commune until I am fifty-seven years old. Or, do I find another priest who is going to give me a little bit more of a “Get Out of Jail Free” card on this issue in my life…

Fr. Meletios: Right .

Steve: … and now I live with guilt and thinking that I’m a spiritual slug because I can’t fulfil the fullness of the life of the Church as it is presented by my traditional spiritual father. So…

Fr. Meletios: The issue is clouded, I think, because of the existence of a couple of books, the one being the Pedalion, the Rudder and the other being of a more recent, at least in English, a more recent date, the Exomologetarion of St. Nicodemos of the Holy Mountain. These books do exist within the Church and always have. But I think their use by, as it were, the general public is a grave mistake. These books are really the textbooks that spiritual fathers consult when they’re stuck on something, but have never, in the experience of our Church, rightly been used as rule books.

Our approach to Canon Law is very similar. I don’t particularly want to get into that whole debate. But there is, within the Orthodox Church, an understanding that canons are where we go when we get in a mess and can’t solve the problem. Then we consult the canons. It’s not like, you know, the Arizona Traffic Manual where you have to pass the test in order to be able to drive a car. And yet, sometimes the mentality I see around the Canons is more like that situation. A list of rules: tell me the rules and I’ll keep them. Well, of course, if you try to keep all the rules, unfortunately you are going to find yourself in some difficulty because the Church has been around for two thousand years plus and there are lots and lots of rules. And some of them may have had some effect in certain ages but not in others and they have reflected always the life of the Church in terms of its place within society. I would say that the giving of penances or epitimia which are aimed at changing someone’s behavior should, indeed, be given if there’s a good chance that it’s going to work. One thing is very important, though. Epitimia must never be given as a punishment. They are always a remedial device, that’s to say, something which can be put in place in order to bring someone back the path, but they are not a punishment of any sort and if for any reason anyone thinks they are a punishment then they need to stop using them altogether, consult with their bishop and move away because that can cause an enormous amount of trouble. That’s straying towards western theology of which we have no part.

Steve: Now how does one go about discerning whether or not the path itself is a legitimate one? And I think this kind of comes around the back door is, usually the questioning begins with questioning the penance and then the larger question is well, the penance was to bring me back to the path but is that path that is being defined by this spiritual father truly the path or is this his own personal issues or, you know, his spiritual pedigree coming out here. How does a convert negotiate those waters when he’s in a parish and he takes communion from this priest and perhaps has no other options but this parish and this priest?

Fr. Meletios: I don’t see a way out of this unless he actually consults somebody else. Usually it would be good to consult somebody else within the same structure, within the same authority structure, as I said before. Perhaps the local dean or indeed the bishop could be consulted. No priest is infallible. No parish priest has autocratic power and if people are in a parishes where either one of those things seems to be the norm, then I recommend that they consult out because that is not the life of the Orthodox Church as she has lived and has been lived through the centuries.

The role of confession is always pastoral, never forensic. There is no sense in which going to confession should arise in some sort of justice. Justice is not what the Church offers; justice is what the world offers.

Mercy is what the Church offers and mercy is only given to people who don’t deserve it. And that must be seen through—transparently, I think—seen through everything the church does pastorly. So it maybe that some—a particular person—needs some encouragement and they are given a rather rigid path to follow. If it can be sort of demonstrated fairly quickly that that would be a good thing to do, for example, someone’s a shoplifter so you say “Well, there’s certain stores you may not go into for a period of time. Let’s see if that makes a difference” and if it does make a difference then you carry on or you broaden your scope or change it to fit the needs of the person concerned. If there is no sense in which the epitimia can actually do any good but is simply accepted as a sort of slap on the wrist, then it’s not an epitimia at all and it must stop.

Steve: So in the confessional, if we can get inside of that a little bit, you said the confessional is not forensic.

Fr. Meletios: It’s not judicial, I think is a better word.

Steve: But forensic, I think, is a good word too. I’ll just be straight out: to what extent is confession confession and to what extent is confession interrogation? How much can a priest legitimately pursue in a confessional situation with someone?

Fr. Meletios: That’s a very difficult question to answer because it depends very much on the personality of the priest concerned and the relationship he has with that particular person.

Steve: Yes, of course.

Fr. Meletios: I have known great confessors who never, ever ask a question. I can’t name them because that would be to break a confidence which I am not able to do.

Steve: And you would have a hundred listeners knocking on their door tomorrow.

Fr. Meletios: Well, I’m afraid many of them are no longer alive, not at least on this earth. I have experienced many times people who ask questions which I personally don’t find very useful and I know that a sort of a sin list sort of thing, a check list is used by some people but I certainly don’t advise that. Confession is essentially a pastoral occasion. The person brings to the confession whatever he or she needs to get off his or her chest. And that really is of the discretion of the person concerned. Legalism, even with the best of intentions, does not demonstrate the life of the Church.

Steve: Now when you say that confession is a pastoral occasion…

Fr. Meletios: As is every other participation in every mystery.

Steve: Absolutely.

Fr. Meletios: It’s not just confession.

Steve: Yes. How much of confession is perhaps more technically counseling?

Fr. Meletios: Well, in certain traditions, presumably the Russian tradition would stand out to you mainly , a lot of people will expect spiritual counseling during confession whereas perhaps on the Greek side, not so much. On the Greek side you confess your sins and you might even get a little sort of little lecture. Both exist within the Church but usually the Greek system, if we can simply simplify everything here—well there are two ways, here—the Greek system works best when you sit in conversation with the spiritual father and have a good, long chat about your circumstances. The question and answer thing I think is intrusive and sometimes it can be abusive, depending on what the questions are. The Russian system of standing side-by-side and facing the icon has another sort of feel about it but again, if it sort of strays from the strictly pastoral then it’s not particularly useful.

Steve: Now, if you go to a confessor and you receive counseling.

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: Are you required, in any way enjoined by the Church or by the relationship to the spiritual father to take the counsel? Is it a sin not to fulfil the advice that he gives you, whatever it is.

Fr. Meletios: There is in the life of the Church, I think, a statement which can only be tested in reality against your own experience, and that is, if you are ever in a position where you are physically or morally in danger then you have the right to do something about it. Obedience in the Church never takes the form of any sort of blind obedience. And as far as I can see, if so long as that the rider, as it were, about being in danger morally or physically, is in place, then you are expected to give it a try. If a priest gives you a piece of advice, you’ve gone to him for advice, then the chances are, that advice will only work if you try it. So if the first thing that you do is to reject it, then the whole purpose of having gone is sort of minimized. However, if you feel that by carrying out the advice you are placing yourself in a state which is either morally objectionable or physically objectionable, then you have every right to either to challenge the priest himself and say “Father, I really don’t think I can do that” or to say nothing to the priest if he’s perhaps, by this time, not prepared to negotiate, and go and consult someone higher up the ladder. There is always, always someone higher up the ladder to consult, even if you go to a patriarch. Then I assume that you can consult the highest authority of all which is an ecumenical council. The fact that they don’t have them very often…

Steve: [Laughter] You are confessing something that an ecumenical council needs to address.

Fr. Meletios: Well, you might be in big trouble. So you are never at a dead end. You’re never in a position where you have to take the advice or die. That isn’t the practice of the Orthodox Church. Now, there are, within the experience of the Church, even in the present day, some men who are so finely tuned spiritually, who are so wise or who are so venerated, that it looks as if they have some sort of infallible dignity. That is not the case. A man who is respected by the whole Church need not necessarily give infallible advice.

The other thing about those special men, and we are talking about a very few. Most people will not meet one. I have met a number of them over the years and one or two of them have played an important part in my life but it’s not an essential part of my life. My life would have gone on without them and I’m grateful that I’ve encountered them. But their position in the Church I think is gravely misunderstood by most people. First of all, the very good ones, the real top-notch spiritual fathers, do not advertise themselves at all, in fact, will deny point-blank that they are spiritual fathers at all and send people away rather than talk to them. We’ve seen this in the history of the Church time and time again and I’ve encountered that, also.

Secondly, it is rarely, if ever, spiritually advisable to approach someone who is so spiritually refined that he may or may not understand the sort of the earthiness of your situation. That’s not a good thing to do.

Steve: Can I paraphrase that or…

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: …ask if this is an accurate paraphrase? So, if I’m hearing you correctly, perhaps a new convert who is just coming into the Church does not necessarily need a refined, clairvoyant elder to make spiritual progress.

Fr. Meletios: I would say it would be rather better that he not find such a person. This is not the daily experience of the Church. Monks may live in a situation where they have close contact with such a person, but monks are in a very different situation from the lay person and the set-up of the monastic life allows them to live in that environment with some degree of safety, which the lay person doesn’t have because he lives in open society.

You mentioned the word “clairvoyant.” I think this is possibly something we need to look at with some care. There is nothing in the Gospels to suggest that God wants us to be able to see with the clarity that he can see. Even Christ himself admits to the fact that he doesn’t know when the end will happen. To want to seek knowledge of things which God obviously does not choose to give us on a regular basis, usually about beginnings and endings, is not necessarily something which should be cultivated in anybody’s spiritual life. Spiritual relationships within the Church are not magical. And the trouble with something like clairvoyance is, it goes straight to the magical, as if people are able to be more spiritual by having power over God, by knowing stuff, rather than by being in a situation where we live in mystery, where God is in firm control. So, the desire for clairvoyance is a big red flag.

Steve: Okay, and I guess a very quick question then is does the grace of ordination or the grace of the priesthood give a man particular power or ability to see things in a confessional situation that he would not otherwise be able to see through his own personal wisdom or ability to discern somebody’s life situation? Will he be able to give some kind of mystical, spiritual advice that he would not otherwise have through his own capabilities?

Fr. Meletios: The way you phrase the question makes it difficult to answer…

Steve: Yes, I know, I’m putting you on the sport. [laughter]

Fr. Meletios: The grace of the Holy Spirit is unlimited in all situations, not just in the confession. But to give the granting of powers which human beings most often do not have is not part of the ordination process. For example, a priest who is ordained doesn’t then have the right to hover three feet off the ground. It may be at some point—and frankly, this is an area in which I am not very comfortable—it may be that his personal sanctity will lead him to a place where he hovers three feet off the ground at some point in his life. And that it has happened in the past, I am quite happy to accept. Why would I not?

Steve: But lay people have done that too…

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: …so it’s not…

Fr. Meletios: No, it’s not.

Steve: … it’s peculiar to the ordination of the priesthood.

Fr. Meletios: No, and just as myrrh-bearing icons, weeping icons, and the like, are signs of tremendous encouragement for some people and not for others, so things like clairvoyance and the personal ability to defy nature may be very important for some people but not for everybody. And when such things do occur, we have to seek very carefully in our own hearts what the significance of such a thing would be for us in particular. It’s usually, I would say, most things like that are given to us by God for personal encouragement and we have to accept them as such. Usually they’re at the personal level where you can’t even talk about them.

Steve: So it could be that in a specific situation with a specific person that grace may be given to a confessor but universally that may not be the case with everybody that he talks to.

Fr. Meletios: And furthermore, there’s nothing in the experience of the Church where it says the man that does hover three feet off the ground when he prays is actually a better confessor than the local parish priest who, you know, smokes cigarettes and has an occasional glass of beer. I mean, that’s the sense in which the Holy Spirit makes up and as I have been known to say before, you know, we must expect God to do things we don’t expect because if we know what he’s going to do next, chances are we simply made him up.

Steve: [laugher] Good point. Very good point We’ve said in the past, “God’s gonna do what he dang well pleases.”

Fr. Meletios: Yes, the dialect is not particularly…

Steve: [laugher] That’s a little more “Texan.”

Fr. Meletios: You’re right. We have, we do have in the Church sentences that are very much like that: “God can do whatever he wants, and he does.”

Steve: Yes.

Fr. Meletios: So as long as we expect him to do whatever he wants then the chances are we are on the right path. When we tell God the paths along which he is allowed to travel and delineate them very carefully, then we are simply tying his hands behind his back.

Steve: Yes.

Fr. Meletios: That’s not what the Church is for at all.

Steve: Along these lines again regarding confession and confessors, a poignant question. I’m aware of more people than I wish I knew who have experienced incredible tragedy in their lives.

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: A lot of time surrounding sexual abuse, physical abuse, and spousal— just horrific things.

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: And as new converts to the Orthodox Church, they look to the fullness of the Church to fulfill their lives and to make straight that which is broken.

Fr. Meletios: Right.

Steve: And the expectation, more often than not with a lot of these folks is that if I take the Sacraments faithfully, I do the disciplines of the Church faithfully, and I find the right spiritual father, then I can find healing. And that sets them on the quest and often on somewhat of a little bit of a—from my perspective—a little bit of an obsessive path to be sure that they are doing everything correctly and doing everything to the fullest of their capabilities and the quest for the right spiritual father begins.

Fr. Meletios: That’s right.

Steve: And more often than not they don’t find that man. And they’re looking for someone that can deal with the incredible tangle of issues that they have in their life now because of the abuse. And of course, what they perceive as, you know, the sin and the brokeness of their lives but also deal with the emotional and psychological issues surrounding that.

A little bit of your background. You’ve been a parish priest for years, decades. You’re also a psychologist, you’re also the abbot of a monastery, you’ve also served as a chancellor of a diocese, so you’re extremely familiar with just about every level of ecclesial and pastoral relationships that a person in the Church in our position could have so given that broad background that you have, what would you say to someone who is in that situation?

Fr. Meletios: It’s very difficult and I think one of the things we have to come to terms with is that the issue of abuse is a fairly modern issue in terms of doing something about it. It tends in the past to have been brushed aside at almost every level, to the detriment of many, many, many people. And that as a Church we don’t really have the mechanics to help someone who is a victim of abuse, anymore than we have anyone who is the victim of cancer. If I want open-heart surgery I don’t go to a spiritual father. And the Church has never said that you should. But the Church will provide everything that you need, from financial support through health and educational issues and that sort of thing. We know that there have been, in the Medieval period in Byzantium, towards the end of the Byzantine Empire, that the churches, the monasteries, were the hospitals that were available to everyone. And they weren’t simply preaching participation in the life of the Church, they were also giving people medicine and performing various procedures, I suppose, to alleviate suffering and so on. Not necessarily things that we would choose to do today but during their period they were thought to be beneficial.

The notion that the Church can provide everything for everyone is simply is not true. The monks of Mt. Athos go to Thessalonika to buy stuff. They don’t rely on the tradition of the Church to present them with, you know, sacks of grain or whatever, from divine helicopters. We have to be realistic about what the Church is and what it’s able to do. What it is able to do, which is outstanding and very exciting spiritually, is to lead people towards the Kingdom of Heaven. What the Church is not able to do is to answer everybody’s problems. That’s what human society is for.

Now whether Orthodox should help other Orthodox more than we do, well, that’s possible. And I’m glad to see in the modern world that things like missionary outreach, IOCC and so on are beginning to happen although they very often make most of their mistakes towards the beginning of their path but that’s sort of to be expected. But that the Church is there to provide a spiritual ambiance in which someone can grow towards the Kingdom, that I do not doubt at all. But as I’ve said, you know, if you need heart surgery then go to a hospital. If you need to heal from abuse, sexual abuse, physical abuse of some sort, whatever, then the chances are you’ll need to see somebody who is trained in helping people to recover from abuse. Simply going to confession will not do it.

I think I know why. And if I might share that. I might be wrong but I think we are all victims of abuse at one level or another. But one of the things about a victim is he has to go on confessing somebody else’s sin in order to get better. And the Church has no provision for doing that. And yet that is precisely the role that the victim finds himself or herself in, carrying enormous amounts of guilt about something that somebody else did. And that requires help. And most parish priests are not really equipped to do that. And most bishops will be absolutely certain that what you need to do is to approach the professionals who know what they’re doing, rather than try to make something out of a parish priest that cannot be done.

Steve: So it’s not antithetical to being Orthodox to seek psychological help, say, join a twelve-step program….

Fr. Meletios: Oh, absolutely not, no.

Steve: …something like that, to basically help in your….

Fr. Meletios: And that person can take their Orthodoxy with them wherever they go. Not in what they say, that’s not what’s required, but in who they are and behave and how they interact with other people. That they can do and bring the light of Christ to other people who haven’t seen it yet. Again, not with what they say but by who they are. So that process, I know, absolutely. Go out into the world. That’s what we do. And if we need to go to the world in order to get help with something, then carry the light of Christ with you as you go.

Steve: Now as a psychologist I know …

Fr. Meletios: I’m not actually a psychologist anymore, but okay.

Steve: …having training in the psychological field, one of the issues that is always presented is if I find a therapist, I need to have a therapist with an Orthodox world view…

Fr. Meletios: Yes.

Steve: … in order to have therapy work with my faith. Are there frameworks of therapy that are neither here nor there when it comes to engaging the Orthodox world view in order to help heal some of the places that the Church doesn’t really go?

Fr. Meletios: I think outside of countries which are Orthodox by nature, like Russia and Greece and so on, you’re going to find it difficult to find someone who has a working knowledge of what the Orthodox world view on anything is.

Steve:: Right.

Fr. Meletios: I mean, most of our lay people, you know, if you ask them “What’s the Orthodox world view on?” Well, it doesn’t actually mean very much to most people. And, if you spend all your life looking for the perfect Orthodox person to be your therapist then the chances are you are going to spend an entire life broken.

So, God’s in charge. Like anything else you can present him with a problem. We’re allowed to do that. We’re encouraged to do that. Why we don’t do it more often I don’t know. We say to God at the end of our morning prayers “I have a problem,, I think I need this, I don’t know what to do about it, you know what to do about it. Please, help me.” And you surrender the outcome to God. This is perfectly Orthodox. And then, once you’ve done that, the miracles start happening. Not necessarily when you want them to, that wouldn’t be right. But with any problem, any problem that we have, we can give to God in that way, allow him to solve the problem and accept the results.

Steve: Well I’m going to have to cut off the interview there. That’s all I have time for this week. Next week: the final segment of my interview with Fr. Meletios on priesthood and spiritual fatherhood. Thanks for joining me; we’ll see you next week.

About

Steve Robinson is heard regularly on Our Life in Christ with his co-host Bill Gould. But in this shorter podcast, Steve reflects on the practical side of being an Orthodox Christian working in a secular environment.

Contributors

Steve Robinson

Steve Robinson